Aaron DeMasi & Sarah E. Berger

Presented at the Conference of the Eastern Psychological Association 2020

Abstract

Infants spend most of their time asleep, therefore, most of their development takes place at night in the crib. Using movement as a window into psychological development, the current study tests the feasibility of manually coding motor behaviors using Nanit video baby monitoring technology to qualify and quantify an infant’s movements in the crib. The method was feasible and showed that, on the night before his first steps, an infant practiced gross motor movements.

Introduction

Infants spend the majority of the first year of life asleep and therefore, the nighttime crib environment is often the primary arena for early human development. Infants babble in the crib at night (Goodlin-Jones et al., 2001) and twitch intensely during REM episodes (Roffwarg et al., 1966). The movements that infants make during sleep appear to be vital for neural development (Tiriac et al., 2014). It is important to study sleep in the context of development because of the amount of time infants spend asleep and because sleep can be a barometer of change in other domains. For example, the onset of new motor skill acquisition disrupts infants’ sleep (Scher, 2005). However, the causal mechanism underlying the relationship between sleep and motor development remains speculative. Is it possible that the kinds of movements infants make in the crib fluctuate as a function of new motor skill acquisition and therefore disrupt sleep? Are they practicing newly learned skills during their night awakenings? The aim of this study is to test the feasibility of behaviorally coding infant movements from video using a new commercially available product, the Nanit video baby monitor, with the longer-term goal of addressing unanswered questions pertaining to the relationship between sleep quality and motor skill onset. To demonstrate the viability of this method, we report the movements of one 325-day-old infant throughout the entirety of the night before he first learned how to walk.

Method

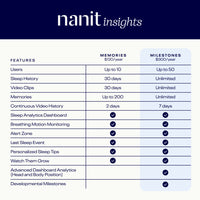

As part of a larger study addressing the link between motor development and nighttime sleep disturbance, parents kept a diary of their infant’s motor milestone attainments and of sleep. Video data was collected using the Nanit video crib monitor, a technology that records video of the infant’s crib and livestreams it directly to the parent’s smart device. Using the diary of one infant (AA), we identified the day he took his first steps. Video from the night prior to walking onset was coded using Datavyu, a video coding software in which researchers can demarcate frequencies and durations of behaviors. Limb (arms, legs, head, trunk) movements and gross motor movements were coded. Limb movements were either isolated (single limb moves without other limbs moving) or simultaneous (limb movement accompanied by movement in other limb(s)). Gross motor movements included body position shifts (e.g., rotating body from supine to prone), postural shifts (e.g., changing to a sitting posture, propping self up on hands

and knees, pulling-to-stand using the crib border, standing up independently), and locomotor movements (e.g., scooting, belly-crawling, crawling, cruising, walking). Durations of each movement were coded but accuracy was limited because the Nanit system records video at a rate of 1 frame per second. Movement was coded whether the infant appeared awake or asleep.

Results

AA was placed in the crib at 7:39 PM and removed from the crib at 7:16 AM. Within this time frame, one hour of data was missing (9:00 PM – 10:00 PM). During the 10 hours and 23 minutes that were coded, AA exhibited a multitude of limb and whole-body movements, even into the late hours of the night. AA moved his arms (independently and with head and trunk) for 13.27 minutes, legs (independently and with head and trunk) for 5.07 minutes and moved his arms and legs simultaneously for 24.55 minutes. AA spent a total of 6.25 minutes shifting his body position (e.g., rolling from prone to supine), 1.25 minutes shifting into and out of a sitting position, and 1.97 minutes rocking his body while sitting. AA spent 2.67 minutes propping himself up on hands-and-knees, 0.67 minutes shifting down from hands-and-knees, and 4.5 minutes rocking on hands-and-knees. He spent 0.52 minutes pulling himself up to stand using the crib rail and 0.37 minutes standing without support. AA also displayed locomotor movements in the crib — he crawled around the crib 6 times for 0.5 minutes total, he cruised twice for 0.25 minutes total, and he bum-shuffled once for 0.03 minutes. AA spent 63 out of 636 minutes (9.9% of his total time in the crib) moving (not including the missing hour). AA moved only 0.93 minutes from 8:00-9:00PM, but spent 27.02 minutes moving from 6:00-7:00AM.

Discussion

This feasibility study demonstrated that Nanit video baby monitoring technology is a promising technology for studying infants’ movements in the crib. Studies have used actigraphy (Scher, 2005) and a combination of a movement detector and behavioral coding separately (Fukumoto et al., 1981) to measure movement during infant sleep. The primary advantage of actigraphy is that it is a non-invasive and objective measure of movement. However, it records no information about kinds of movement taking place and is influenced by external artifacts (i.e., the parent picking up the infant). Fukumoto et al. (1981) utilized a body movement detector placed under the infant’s bed to measure movement, in combination with visually qualifying movements into three categories (gross movements, limb movements, and twitch movements). This method of studying infant movement was highly informative and provided an objective account of body movement durations, however, they did not use video recording, so researchers had to code accurately in the moment and could not replay events. The behavioral coding of infant movement of the current study, while more labor intensive than employing an automatic method, succeeded in describing a wide array of infant movements in the crib, and the primary advantage of this method is its specificity in qualifying movement. This demonstration begs for more research to be done investigating the kinds of movements infants make in the crib when they learn new motor skills, as it appears from our descriptive analysis that a wide variety of infant movements are observable utilizing Nanit video baby monitoring technology. The infant displayed multiple bouts of overt full-body movement on the night before he learned to walk. Future studies will investigate whether the movements differ before, during, and after infants acquire new motor skills and how the onsets of those skills influence sleep quality.

About the Researchers

The researchers included Aaron DeMasi and Sarah E. Berger.

- Dr. Sarah Berger is a Professor of Psychology at the College of Staten Island and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. She received her PhD from New York University. Dr. Berger was an American Association of University Women Postdoctoral Research Fellow and a Fulbright Research Scholar. Dr. Berger studies the interaction between cognitive and motor development in infancy, particularly response inhibition and its implications for the allocation of attention in very young children. A line of National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded work, in collaboration with Dr. Anat Scher, has been the first to study the impact of sleep on motor problem solving in infancy.

References

Fukumoto, M., Mochizuki, N., Takeishi, M., Nomura, Y., & Segawa, M. (1981). Studies of body movements during night sleep in infancy. Brain Development, 3(1), 37-43.

Goodlin-Jones, B. L., Burnham, M. M., Gaylor, E. E., & Anders, T. F. (2001). Night waking, sleep-wake organization, and self-soothing in the first year of life. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: 22(4), 226–233.

Roffwarg, H. P., Muzio, J. N., & Dement, W. C. (1966). Ontogenetic development of the sleep-dream cycle. Science: 152(3722) 604-619.

Scher, A. (2005). Crawling in and out of sleep. Infant and Child Development: 14(5), 491-500.

Tiriac, A., Rio-Bermudez, C.D., & Blumberg, M.S. (2014). Self-Generated Movements with “Unexpected” Sensory Consequences. Current Biology, 24, 2136-2141.